|

|

April – June, 1978

| Huna Research Associates Dr. E. Otha Wingo, Editor 126 Camellia Drive Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 |

The Max Freedom Long Library Dolly Ware, Curator 1501 Thomas Place Fort Worth, TX 76107 |

Dear Huna Research Associates:

One of the key ideas of the Huna system is NORMAL LIVING in every way. Huna emphasizes the practical, rather than the theoretical. We can learn to live more effectively on the middle self level by coordinating the roles of the three selves. Thus we are to live normal lives, but our lives will be more efficient through the use of Huna. It could also be called a type of “natural” living, or living with nature.

We have the prime example of those who “live with nature” — right in our own back yards, so to speak. The American Indian has much in common with the ancient Polynesians. We may even now find the equivalent of the Hawaiian kahuna in the American Indian “medicine man.”

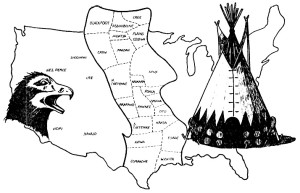

There is much to learn from these original, native Americans. Keep in mind that there is not a “typical American Indian.” With many different tribes and distinctive customs, each should be studied on an individual basis.

The feature article in this issue provides a glimpse into the Plains Indian, primarily, who lives with nature in a unique way as a result of his Identifying Vision.

The North American Indians are allegedly the most natural people to inhabit the Earth since antiquity. To them, the two-legged, the four-legged, and all green things are of one mother, Mother Earth, and of one father, the Great Spirit. Recognizing the balance and interdependence of all nature, the Indian readily became a partner of natural existence — living upon this Earth as a unitary part of life.

The North American Indians are allegedly the most natural people to inhabit the Earth since antiquity. To them, the two-legged, the four-legged, and all green things are of one mother, Mother Earth, and of one father, the Great Spirit. Recognizing the balance and interdependence of all nature, the Indian readily became a partner of natural existence — living upon this Earth as a unitary part of life.

Their most sacred animal, the buffalo, was also their staple. Their tipis, beds, blankets and clothing were made of his hide. His flesh strengthened them as it became part of their flesh. His stomach was made into their kettles. His horns, their spoons. His bones, their knives and the women’s awls and needles. Out of his sinews they made their thread and bow strings. His hooves became their rattles. And his mighty skull, with the pipe leaning against it, was their sacred altar. As the lives of the Indian and the buffalo became interlaced, they shared the same prairie, the same nomadic life-style, the same reservations — and the same fate.

Prior to the intrusion of the white man, there was a time of peace upon the plains. With plenty of land and game for everyone, most quarrels were trivial at most. As a rule, the object in battle was not necessarily to kill, but to “count coup” — striking the enemy with a stick and shaming him. The Indians believed it took much more courage to come face-to-face with the enemy and disgrace him than to kill at a distance. This was the way he earned the respect of his people and was honored by the women. For the bravest warrior of the tribe — the one who had counted the most coups — to have never killed was not unusual. Perhaps it is fortunate for the white man that the Indians took this playful approach to warfare, each fighting as an individual to prove his own strength and courage. For the Plains Indians constituted the best light cavalrymen the world has ever known. Had they united against our soldiers and settlers, the result might have been somewhat different.

Many writers, without going beyond the externals of the Indians’ way of life, simply describe them as primitive and pagan. But pagan implies one who lives close to nature and primitive literally means first. These words do not mean savage or ignorant. Man is in a constant state of evolution. Therefore we say that the Indians have not “evolved” to the level that we have. But by the same token they were much closer to our source spiritually as well!

Traditional Indian philosophy views human life as a part of the process of nature and the individual being a complete microcosmic representation of the universe. Thus, they learned about their own nature from nature herself. To the Indians, strength and survival depended not upon the ability to manipulate and control nature, but upon an ability to harmonize with Her as an integral part of the system of life.

Shaped by a natural religion based on their native and wild surroundings, their standard of wisdom and learning became that of nature and of the wise, old men of their tribe. Like the eternal rocks and the crystal streams, like the white clouds and green trees, the Indian was a part of nature. He became so because he studied the whole of it until little escaped his mind, and then sought to move with Her in a rare kind of conformity. While their scientific know-how will not compare favorably with the monumental accomplishment of our technology, they received a reverence for life which is most impressive and practical, for it reveals the marvelous appreciation they had for every created thing in the universe.

In the Indian’s way of thinking, all life is circular: the Earth, sun, stars, moon, horizon, rainbows — all circles within circles; no beginning and no end. Timeless and flowing, with new life emerging from death. The circle stood for the togetherness of people as they sat around the campfire passing the pipe. They danced in a circle. Their tipis were circular and united in the circle of the village, which in turn was joined in the circle of their nation. The circle literally bound them together, to work and share with one another. And this was symbolized by the nation’s sacred “hoop of life.”4

Their most common forms of tribal government were designed to promote the worth and freedom of the individual. While distinctions of rank were established and maintained for good order, there were no hidebound hereditary classes, no economic classes, and no servants or slaves. In the Indian’s view, personal aggressiveness could bring anyone to a position of wealth and high standing. Hence, to begin life as a social nobody and strive for spiritual blessings through visions and to distinguish himself as a tribe protector was the goal of the average warrior.3

Their most common forms of tribal government were designed to promote the worth and freedom of the individual. While distinctions of rank were established and maintained for good order, there were no hidebound hereditary classes, no economic classes, and no servants or slaves. In the Indian’s view, personal aggressiveness could bring anyone to a position of wealth and high standing. Hence, to begin life as a social nobody and strive for spiritual blessings through visions and to distinguish himself as a tribe protector was the goal of the average warrior.3

Even the status of chief had few compensations attached to it. It was honorary, but also laborious and frequently an unappreciated task. While he might occasionally assume the ceremonial regalia of his office, for the most part he had to secure and maintain his living and position in the same manner as his fellow tribesmen. He had to be one with his people, not above them. Indian leaders were sincere, many times sharing their own personal belongings with their tribe. They had to give to their people with one hand what they had obtained with the other. Greed, as it is understood in the materialistic terms of today, was seldom present on the plains. Charity, next to the brave deeds necessary to preserve the tribe, was the basis for achieving and maintaining a high standing among the Indians.

Lame Deer, chief and medicine man of the Lakota Sioux, comments on this:

Before our white brothers came to civilize us we had no jails. Therefore we had no criminals. You can’t have criminals without a jail. We had no locks or keys, and so we had no thieves. If a man was so poor that he had no horse, tipi or blanket, someone gave him these things. We were too uncivilized to set much value on personal belongings. We wanted to have things only in order to give them away. We had no money, and therefore a man’s worth couldn’t be measured by it. We had no written law, no attorneys or politicians, therefore we couldn’t cheat. We really were in a bad way before the white man came, and I don’t know how we managed to get along without the basic things which, we are told, are absolutely necessary to make a civilized society.2 [pp. 63-64]

The Indians are invariably a deeply religious people. But although their religion was participated in fervently by everyone, it remained an individual and personal matter of the greatest portent. For there was only one inevitable duty in the life of the Plains Indian — the duty of prayer.

He awakes at daybreak, puts on his moccasins and steps down to the water’s edge. Here he throws handfuls of clear, cold water into his face or plunges in bodily. After the bath, he stands erect before the advancing dawn, facing the sun as it dances upon the horizon and offers his unspoken orison. His mate may precede or follow him in his devotions, but never accompanies him. Each soul must meet the morning sun, the new, sweet earth and the Great Silence alone.3

Religion was at the very core of the Indian’s existence. All they undertook began with and was thereafter influenced by this principle. It is a truth which applies to everything from child raising to crafts, from community relationships to warfare, and from philosophy to story-telling. The entrance of their lodges even faced east to remind the awakening warrior to pray to the dawning sun and the “One Above.” Every new day came as a holy event and he must first give thanks for his strength, his family, his tribe and his nation.

Religion was at the very core of the Indian’s existence. All they undertook began with and was thereafter influenced by this principle. It is a truth which applies to everything from child raising to crafts, from community relationships to warfare, and from philosophy to story-telling. The entrance of their lodges even faced east to remind the awakening warrior to pray to the dawning sun and the “One Above.” Every new day came as a holy event and he must first give thanks for his strength, his family, his tribe and his nation.

The Indians believed in bringing the young along to take their place because this is Nature’s way. Customs and knowledge were handed down from parent to child, the teaching and learning going back to the beginning of time. It may be this willingness to share truth with the young that made the elders loved and respected, which in turn made talk easy between the generations.

Our people were wise. They never neglected the young or failed to keep before them deeds done by illustrious men of the tribe. Our teachers were willing and thorough. All were quick to praise excellence without speaking a word that might break the spirit of a boy who might be less capable than others. The boy who failed at any lesson only received more lessons and care, until he was as far as he could go.

The youth who thinks first of himself and forgets the old will never prosper; nothing will go straight for him.

A man who is not industrious will always have to borrow from others and will never have things of his own. He will be envious and tempted to steal. He will be unhappy. The energetic man is happy and pleasant to speak with; he is remembered and visited on his deathbed. But no one mourns for the lazy man.

A thrifty woman has a good tipi; all her tools are the best; so is her clothing.3

When a young girl had her period for the first time, her parents treated the event as something sacred which made her into a woman. She was honored with a feast, inviting everyone and having a big give-away of presents.

At puberty, the young men would go on a Vision Quest for their identity in life. Isolated on a distant hilltop or lowered into a pit in the ground with only his moccasins, breech-clout and a few symbolic objects, the young brave is separated from the everyday world by a loneliness which forces him to withdraw deep into himself, fasting and praying for a vision of guidance. After the third or fourth day of his Vision Quest, he would return to his village and tell his “Spiritual Fathers” of his experiences. His Fathers would interpret these experiences in terms of what they reflected of the seeker’s character and place him upon the path of fulfilling his purpose in life. They would then give him a name which symbolically represented these things and construct for him a shield that visually reflected the same symbolic meanings. A person’s name and shield revealed everything about him: who he was, what he sought to be, his loves, fears, dreams, etc. These shields were carried among the people in order that anyone they met might know them. Even when they rested in their lodges, their shields were hung outside for all to see.5

At puberty, the young men would go on a Vision Quest for their identity in life. Isolated on a distant hilltop or lowered into a pit in the ground with only his moccasins, breech-clout and a few symbolic objects, the young brave is separated from the everyday world by a loneliness which forces him to withdraw deep into himself, fasting and praying for a vision of guidance. After the third or fourth day of his Vision Quest, he would return to his village and tell his “Spiritual Fathers” of his experiences. His Fathers would interpret these experiences in terms of what they reflected of the seeker’s character and place him upon the path of fulfilling his purpose in life. They would then give him a name which symbolically represented these things and construct for him a shield that visually reflected the same symbolic meanings. A person’s name and shield revealed everything about him: who he was, what he sought to be, his loves, fears, dreams, etc. These shields were carried among the people in order that anyone they met might know them. Even when they rested in their lodges, their shields were hung outside for all to see.5

Visions have been important to the Indians as far back as legend imparts — so much a part of their life that one could almost say that a man with no vision can’t be a real Indian. And these visions weren’t merely dreams, but insight which they paid for dearly, many times through the pain of their own bodies. Pain was something very real to them — a part of life to be experienced, not shunned and feared. The idea of enduring pain so that others may live should not strike you as strange. Do you not, in your churches, pray to one who is “pierced,” nailed to a cross for the sake of his people? No Indian ever called a white man uncivilized for his beliefs or forbade him to worship as he pleased.

The difference between the white man and us is this: You believe in the redeeming powers of suffering, if this suffering was done by somebody else, far away, two thousand years ago. We believe that [it] is up to every one of us to help each other, even through the pain of our bodies. Pain to us is not “abstract,” but very real. We do not lay this burden onto our god, nor do we want to miss being face-to-face with the spirit power. It is when we are fasting on the hilltop, or tearing our flesh at the sun dance, that we experience the sudden insight, come closest to the mind of the Great Spirit. Insight does not come cheaply, and we want no angel or saint to gain it for us and give it to us secondhand.2

The honesty involved in such an undertaking as the vision was of prime importance. No Indian would risk deluding himself about a vision. The result would be a catastrophe and bad luck would plague his every step. Being so convinced of this, his thought patterns led him to guarantee that it would be so.

Chiefs, priests, medicine men, shamans, warriors, braves, hunters — all helped along the path of life by their visions. These revelations came to them through representatives of the plant and animal kingdoms and were believed to be the media for the power of the Great Spirit. These symbolic “helpers” became sacred to the individual whose visions they appeared in and a kind of father-child relationship evolved between the two. A “helper” might teach his seeker a word-power song, or instruct him how to dress for battle or impose certain taboos in diet or behavior. Once an Indian had received his helper in a vision, he always carried a token of his patron with him. In the Indian’s mind, garments and amulets made from the physical counterpart of his “helpers” served to increase his confidence in the close relationship he envisioned to exist between them.3

When the early explorers and trappers came upon the Indians, they encountered many phenomena which they could not comprehend. So they began to refer to the Indians who performed such unexplainable feats as “medecin” the French word for physician. Its similarity in sound to the English word “medicine” made the term easily adoptable by the English-speaking people, so that “medicine” came to mean the unexplainable power and “medicine man” the person who controlled this power. Unfortunately, the word “medicine” came to describe every form of Indian mystical practice. However, a careful examination shows there were distinct categories of practitioners; their only common bond was that they began their careers with visions and employed constant prayer as supplication.

There were several classes of healers: a medicine man might specialize as a herbalist, chewing the herb into a bolus and placing it on the wound; the “tied-one” who uses the power of rawhide and stones to cure and to find game; or the conjurer, which we have come to know as the “witch doctor” who sucks the evil out of the body and spits it into a substance that is later destroyed. There was a specialist who performed minor surgery. And all medicine men carried their paraphernalia in a “medicine bundle” which was assembled at the advice of their “helpers.” There were the “man of vision” who was given the power of prophesy and could foretell events of the future; the “sacred-clown” whose task it was to lift the spirits of the people in time of depression; and the “holy men” who loved the silence — a silence with a voice like thunder which told them of many things.

Being a medicine man, more than anything else, is a state of mind, a way of looking at and understanding this Earth, a sense of what it is all about.2

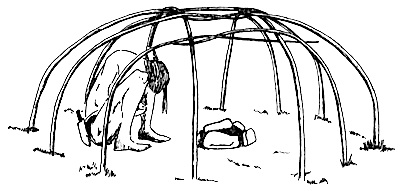

Before any healing or ceremony, the holy men and doctors must first purify body and soul, in order to become fit vessels for the “Great One Above.” The most common method of purification used among the Plains Indians was done in the Sweat Lodge. A small, frame dome was constructed out of saplings and sealed up with hides. In the center of the Lodge was piled red-hot stones. Water was poured over the stones, causing steam and profusely sweating the impurities out of the body and mind.4 The Sweat Lodge played a vital role in the Indian scheme of life, for it was considered to be the first step in the link between man and his God.

Before any healing or ceremony, the holy men and doctors must first purify body and soul, in order to become fit vessels for the “Great One Above.” The most common method of purification used among the Plains Indians was done in the Sweat Lodge. A small, frame dome was constructed out of saplings and sealed up with hides. In the center of the Lodge was piled red-hot stones. Water was poured over the stones, causing steam and profusely sweating the impurities out of the body and mind.4 The Sweat Lodge played a vital role in the Indian scheme of life, for it was considered to be the first step in the link between man and his God.

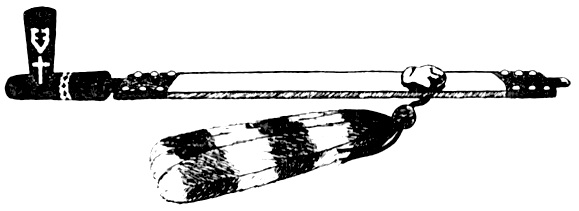

Once cleansed, the medicine man would adorn himself with the images of his visions and approach the Great Spirit with his request. The implement used among the Indians to make contact with the “One Who Made All Things” was the pipe. When the Indian smoked the pipe, he was at the center of life. As the smoke was released and drifted skyward, he was giving a part of himself to the Great Spirit and every living creature upon the Earth. However, this flow was not one-way, but an exchange. Power from the Great Spirit also flowed down through that smoke, through the stem and right into the body. In this fashion, the Indians believed the pipe was alive and sacred. Upon completion of his request, the medicine man carefully empties the ashes from the pipe and separates the stem from the bowl. With this action he breaks the tie which binds Earth and Heaven together. Separated like this, the pipe is no longer alive and sacred, but just another possession.2

The Indians did not believe that the breath of the Great Spirit was something unique to them alone, but a universal “Power” drawn upon by all life. The utilization of this energy became rudimentary in their healing and ceremonies. Much of the Indian’s optimism regarding success rested on the principle that imitation of a desired event in exact detail could produce it. The mass spirit of their dances and ceremonies were not only designed to depict their request. It also raised the emotional energy of the aggregate, reinforcing their requisition to the Great Spirit.4 Their most commonly practiced medical procedures also employed this energy. The medicine men would breathe vigorously and blow their breath onto the wound or part of the body thought to correspond with the internal malady.3 The present- day Hopi medicine men learn to consciously accumulate and manipulate this energy in meditation and refer to the medium which transfers it as “tubes.”6 In fact, all Indian medicine and holy men give top priority to the capacity to control the attention — to maintain one pointedness of mind as to make free communication with the “Spirit Power.” Rolling Thunder, medicine man and spokesman for the Shoshone, is currently being researched by the Menninger Foundation in the study of “voluntary control of internal states.” Addressing the Foundation, Rolling Thunder made the following remarks about this energy:

The human body is divided into two halves, plus and minus. Every whole thing is made of two opposite halves. Every energy body consists of two poles, positive and negative. We can control this energy [mana] just like we learn to control our physical bodies; and by controlling this energy we produce forces [aka cords]. We can learn to control these forces.

… You’ve seen me spit on the palms of my hands, and hold them up and slap them together. At least that’s what it looks like to you, right? That has its own use and its own meaning, but you might say it’s a kind of a helper [physical stimulus]…

At that moment I could lay one hand on a man and give him a dangerous jolt, and I don’t mean just on the bottom level. So it’s possible to do great harm…

The same principles are always at work — the same techniques— and they can be used for good purposes or for bad. So there’s good medicine and there’s bad medicine…

As long as so many people accept this modern-day competition, willing to profit at the cost of others and believing it’s a good thing; as long as we continue this habit of exploitation, using other people and other life, using nature in selfish, unnatural ways; as long as we have hunters in these hills drinking whiskey and killing other life for entertainment, spiritual techniques and powers are potentially dangerous. The medicine men and traditional Indians who know many things know also that many things are not to be revealed at this time.

The establishment people think they have a pretty advanced civilization here. Well, technically maybe they’ve done a lot, although we know of civilizations that have gone much further in the same direction. In most respects this is a pretty backward civilization. The establishment people seem completely incapable of learning some of the basic truths.

The most basic principle of all is that of not harming others, and that includes all people and all life and all things. It means not controlling or manipulating others, not trying to manage their affairs. It means not going off to some other land and killing people over there — not for religion or politics or military exercises or any other excuse. No being has the right to harm or control any other being. No individual or government has the right to force others to join or participate in any group or system or to force others to go to school, to church or to war. Every being has the right to live his own life in his own way.

Every being has an identity and a purpose. To live up to his purpose, every being has the power of self-control, and that’s where spiritual power begins.

In all Indian healing, the utmost importance is placed on the psychological condition of the patient, his way of perceiving and relating to life. I am beginning to think, continues Rolling Thunder, that all of one’s condition, including one’s body and one’s environment, is in the mind and that the changes that take place in the external world occur first in the mind.1

A true medicine man always considers a man’s karma and destiny before accepting a case. He must first look into and understand what is meant to be according to each individual’s own progress and unfoldment. If he couldn’t remove the handicaps, or even felt it undesirable to do so, he might work towards bettering the patient’s relationship to that condition.

The life of all Indians was very much influenced by interest in the “spirit world.” They believed in the immortality of the soul and sometimes in dreams and visions, glimpses came which they felt were insights into the “life-after.” There was the Ghost Dance, in which they would dance themselves into a trance and talk to their deceased relatives. There were mediums among the tribes who would go into trance and the dead could communicate through them. Or advice about a specific cure might be sought from the spirit world by a medicine man, many of which even considered themselves to be channels of healing for the “other side.” And the possibility of possession by an outside entity was always taken into consideration, with a form of exorcism being a composite part of their approach to healing. Although we judge the Indian’s understanding of the “happy hunting ground” to be vague and hazy at times, this  troubled them little, for they accepted the fact that a finite being cannot understand much about an infinite place or person.

troubled them little, for they accepted the fact that a finite being cannot understand much about an infinite place or person.

They never built churches or composed a book of sacred writings. They had no holy days or Sabbath, no prayer books or hymnals and no hell or pearly gates. Yet all they owned and every act of their lives were imbued with their religion — a religion of self-reflection intertwined with the elements of nature. For to the Indian, the material life was not primary, but only the instrument through which he learned and evolved. Hyemeyohsts Storm speaks of this growth in Seven Arrows:

We must all follow our Vision Quest to discover ourselves, to learn how we perceive of ourselves, and to find our relationship with the world around us. Among the People, a child’s first Teaching is of the Four Great Powers of the Medicine Wheel.

To the North on the Medicine Wheel is found Wisdom. The Color of the Wisdom of the North is White, and its Medicine Animal is the Buffalo. The South is represented by the Sign of the Mouse, and its Medicine Color is Green. The South is the place of Innocence and Trust, and for perceiving closely our nature of heart. In the West is the Sign of the Bear. The West is the Looks-Within Place, which speaks of the Introspective nature of man. The Color of this Place is Black. The East is marked by the Sign of the Eagle. It is the Place of Illumination, where we can see things clearly far and wide. Its Color is the Gold of the Morning Star.

At birth, each of us is given a particular Beginning Place within these Four Great Directions on the Medicine Wheel.

This Starting Place gives us our first way of perceiving things, which will then be our easiest and most natural way throughout our lives.

But any person who perceives from only one of these Four Great Directions will remain just a partial man. For example, a man who possesses only the Gift of the North will be wise. But he will be a cold man, a man without feeling. And the man who lives only in the East will have the clear, farsighted vision of the Eagle, but he will never be close to things. This man will feel separated, high above life, and will never understand or believe that he can be touched by anything.

A man or woman who perceives only from the West will go over the same thought again and again in their mind, and will always be undecided. And if a person has only the Gift of

the South, he will see everything with the eyes of a Mouse. He will be too close to the ground and too nearsighted to see anything except whatever is right in front of him, touching his whiskers.

There are many people who have two or three of these Gifts, but these people still are not Whole. A man might be a Bear person from the East, or an Eagle person of the South. The first of these men would have the Gift of seeing Introspectively within Illumination, but he would lack the Gifts of Touching and Wisdom. The second would be able to see clearly and far, like the Eagle, within Trust and Innocence. But he would still not know of the things of the North, nor of the Looks-Within Place.

In this same way, a person might also be a Golden Bear of the North, or a Black Eagle of the South. But none of these people would yet be Whole. After each of us has learned of our Beginning Gift, our First Place on the Medicine Wheel, we then must Grow by Seeking Understanding in each of the Four Great Ways. Only in this way can we become Full, capable of Balance and Decision in what we do.5 [pp.5-7]

Rolling Thunder discusses our mutual purpose in life, and our transitions on the path of evolution:

We are born with a purpose in life and we have to fulfill that purpose. Some of our young men go out when they are twelve or thirteen years old and pray and fast at a certain sacred place. They learn their purpose in life. Now we hear of the new young people talking about finding their identity, their place in life, and they are very wise to do that, if they can do it. Some of them have, I think, and they are now trying to make things better for other people, which is our only purpose in this life — to share with others.

We live many lives. We go through different lives; and sometimes we are able to put together the different lives. That is the way it is. We go from one life to another and we should have no fear of death. It is just a transition.

Those who are able to work with concepts of psychic healing and other psychic phenomena would no doubt welcome much more workable hypotheses than the story of the devil and the pearly gates or the postulation that the path of life is from death to death, from nothingness to oblivion. But perhaps they did not expect to hear about reincarnation from an American Indian. Yet this has been a major concept or view of life held by virtually all ancient cultures….

I have done some studying of your history, too, and I know that there are some of your people… who still believe in the old ways. But some of your ancestors, who came here from that land across the water, conjured up a hell and a devil. That did not exist before, but they conjured it up — because if you believe in something, and believe it long enough, it will come into being. So they created that and they brought it here with them, and we Indians don’t want any part of it.

These things we call false teachings. They teach us to fear, to be afraid that we are going to be punished. This is why a person grows up with fears and anxieties and later finds himself seeing a psychiatrist. 1[pp. 262-263]

An old Indian proverb offers a solution to the ever increasing vexations among people and nations:

There can never be peace between nations until there is first known that true peace which is within the souls of men. This comes when men realize their oneness with the universe and all its Powers, and when they know that the Great Spirit is at its center, that all things are his works, and that this center is really everywhere; it is within each of us. He watches over and sustains all life. His breath gives life; it is from him and to him that all generations come and go.

Every step we take upon mother earth should be done in a sacred manner; each step should be as a prayer. The power of a pure and good soul is planted as a seed and will grow in man’s heart as he walks in a holy manner.3

Disenchanted with the material overtones of our society, many zealously await the Easternization of the West — the day when the Oriental philosophies replace the selfish exploitation of the Occident. We listen to the yogis, swamis, and lamas tell us to work internally and to withdraw the mind’s attention from the external world. Withdraw, withdraw, they say. In this way one identifies with the self within — the Atman or cosmic mind. But the Indian approach is to work externally, to sharpen the senses and to embrace the world. For man is in and of nature — a microcosm of a universe he can relate to and learn from. While these may simply be different expressions of the same self-knowledge, the Indians believed that only through interaction with his environment could he learn of the natural world, thus becoming one with himself and his parents, the Great Spirit and mother earth.1

Disenchanted with the material overtones of our society, many zealously await the Easternization of the West — the day when the Oriental philosophies replace the selfish exploitation of the Occident. We listen to the yogis, swamis, and lamas tell us to work internally and to withdraw the mind’s attention from the external world. Withdraw, withdraw, they say. In this way one identifies with the self within — the Atman or cosmic mind. But the Indian approach is to work externally, to sharpen the senses and to embrace the world. For man is in and of nature — a microcosm of a universe he can relate to and learn from. While these may simply be different expressions of the same self-knowledge, the Indians believed that only through interaction with his environment could he learn of the natural world, thus becoming one with himself and his parents, the Great Spirit and mother earth.1

Through Huna we learn that the path to enlightenment is not trod by withdrawing into a monastic lifestyle and pretending to be supraliminal, but by recognizing the different levels of consciousness and integrating them into our daily lives. The Indian did not teach to withdraw from the elements of life, but rather to harmonize them within himself. His goal was to become “whole.” He viewed the physical, psychological and spiritual collectively and did not attempt to isolate them, for to do so would be “unholy.”

The first major objective in the life of the Indian was to find his identity, his purpose. Then he pursued that purpose through visions and appeals to the Great Spirit via his “helpers.” These subconscious “helpers” were evoked by the physical stimuli of herbs, special stones, antlers, eagle’s heads and claws, bear paws and the pipe, the instrument through which he approached the High Self. And all of this was effective because he lived the “hurtless life” and took specific measures to purge the guilt from his low self, be it in the Sweat Lodge or with a morning dip at the water’s edge.

To the Indians there are no weeds or dangerous plants, no poisonous snakes or vicious animals, and no unwanted rains or upheavals. He views all of these elements as essential for the balance of nature. Since birth he learns to expand his consciousness to include these things within his very being. For once man begins to identify himself with the plants and animals, Mother Earth, his fellow man and all manifestations of the life force, only then will he be able to relate ecology, health and politics to each other and to the world at large.

The laws of karma, of action-reaction, man-nature relationships and all natural laws, principles of health and healing, self-regulation and social interaction can be understood only when they are seen collectively… For example, the ever increasing accumulation of complicated and oppressive laws which have the effect of obscuring individuality and obstructing self-determination and self-regulation results from growing inattentiveness to the laws of mind and nature. In a vicious circle, these man-made laws obscure the laws of nature and promote further ignorance resulting in further chaos resulting in the apparent need for further oppression.1 [p. 41]

Relegating the Indians onto reservations and stripping them of their natural habitat, many oppressors felt confident they had silenced the Indian faith.

But the old medicine men were not fooled. They knew that the sacred “hoop of life” was not broken and that the Spirit Power would some day return to this planet. And now they see it coming back strong. One omen is the recent research done by the Menninger Foundation into the healing methods of such traditional medicine men as Rolling Thunder. Addressing the Foundation, Rolling Thunder commented:

Of course there are things these doctors up at Menninger Foundation know that I don’t know, but there are a lot of things they don’t know, and these are things that I could help with. Some of these things might sound strange to these doctors, like some of the cases they call “schizophrenia” and some other cases, where people are influenced by other beings. Sometimes a part of a person’s energy is taken by another, sometimes people get spaced out on drugs and things and other beings come in and try to take over, and sometimes two spirits try to occupy one body. Doctors’ training is very limited and they have little awareness or curiosity outside their training. Some of them are even trained to be cynical. But they have no need to go by their feelings; they have a chance, now, to see how these things work. It’s high time doctors and medicine men started working together.1 [p. 162]

The following notice appeared in the February 1978 issue Of East-West Journal:

COOPERATIVE HEALING

Traditional Navajo healers blessed a medical clinic in the remote western reservation community of Rough Rock, Arizona, in December. Following morning ceremonies, the medicine men moved into the clinic to practice their healing arts alongside physicians from the Indian Health Service. This is believed to be the first time modern doctors and Indian healers have worked side-by-side.

The medicine men are instructors at the local school for medicine men initiated in 1968 on a federal grant. Since then, eight students have graduated, and six have dropped out. Six local medicine men serve as instructors.

John Dick, director of the traditional school, hailed the new arrangement. “If they can’t cure somebody, they send them to us; those we can’t help, we send to them.

FEBRUARY 1978/EASTWEST

Another auspicious sign is by Indians. In the past, tensions have hindered communications between the two cultures, but now the rights of minorities are breaking down these barriers. Many medicine men who have so long remained silent are coming forward and sharing their teachings.

The Hopi of Arizona are thought to be custodians of the spiritual doctrine of the North American Indians. Their very existence in a region completely at the mercy of the elements attests to this fact. These teachings and prophecies are written down and kept secret in Hopi villages and are known to be quoted by traditional Indians from all over. These prophecies predicted the major wars, the recent manipulation of governments in the Far East and the creation of the UN Headquarters on Manhattan Island (“The Land of the Iroquois”). They presaged the moon landings, space stations, the increasing ecological desecration of the continent and the constant oppression of sovereign people living up on this land. The Hopi accurately estimate the timing of these events with a comprehensive knowledge of all the principles and signs of nature related to the foretold conditions. The ultimate hope and help for the oppressed native people and continual abuse of this continent, say the prophecies, is to come from the light- skinned people themselves, from the sons and daughters of the oppressors. A generation would emerge who would once again respect nature and search inward to find their identity in life, many of whom would even begin to wear long hair and headbands as the Hopi do. And these people, state the prophecies, will be the first true friends of the Indians.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Boyd, Doug, Rolling Thunder. Dell Publishing Co.: New York, 1974. 273 pp., $3.45.

This project began as a report to the Voluntary Controls Program of the Menninger Foundation’s Research Dept., but immediately became much more. By living next to and observing Rolling Thunder, Doug Boyd has captured the uniqueness of a Shoshone shaman who “cures disease and heals wounds, makes rain and thunder appear out of nowhere, performs exorcisms, transports objects through the air, and communicates with other medicine men unaided by technology.”

“Though I must admit I have written with the bias of an admirer, I have been able to tell more than he would have said about himself. Not that I have told his secrets, for I don’t know them — I have shared only what many others have also observed — but I have been able to say, for example that he is a healer and spiritual leader, and Rolling Thunder would not have called himself these things.” [p. viii]

- Lame Deer, John (Fire), and Richard Erdoes, Lame Deer: Seeker of Visions. Pocket Books: New York, 1972. 277 pp., $1.95.

“Storyteller, rebel, medicine man, Lame Deer was born seventy years ago on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, a full-blooded Sioux. He has been many things in a white man’s world — rodeo clown, painter, sheep- herder, as well as prisoner and policeman. But, above all, and despite the twentieth century, he is a wicasa wakan, a holy man of the Lakota tribe.

“With a tremendous gift for anecdote, Lame Deer tells of his childhood and the youthful vision that molded his life, his harsh days in a white man’s school where he was taught ‘not to to an Indian,’ his reckless young manhood, shotgun marriage and divorce, the history and folklore of the Sioux, and his fierce struggle to keep alive the pride and culture of a defeated people, still living as strangers in their own land.” [Blurb]

- Mails, Thomas E., The Mystic Warriors o f the Plains. Doubleday and Company, Inc.: Garden City, N.Y., 1972. 618 pp., $25.00.

One of the best books on the native Americans by a non-Indian. Thomas Mails has done extensive research into the Plains Indians and presents his finding in 618 pages of text, 32 full-color illustrations and nearly 1,000 detailed drawings. In this scholarly work is contained a complete bibliography, index, and notes — an excellent reference source.

“The Mystic Warriors of the Plains describes in detail the life ways and life styles of the Plains Indians at the height of their culture, when they were still relatively untouched by the white man’s progress. Here are their day-to-day activities, their social customs, their form of government, the training of their young, and the role of warrior in their highly mobile society. A large section of the book is devoted to their religion, their supernatural beliefs, the practice of medicine, their vision seeking and their ceremonial practices. Another major section is devoted to their arts and crafts; another to the making of their clothing, shelters, tools and weapons.” [Dust Cover]

- Neihardt, John G., Black Elk Speaks. Pocket Books, New York, 1977. 238 pp., $1.95.

From the Battle of the Little Big Horn to the last terrible massacre of the Indians at Wounded Knee, Black Elk, warrior and medicine man of the Oglala Sioux, lived and witnessed the life and death of the Plains Indian. This book is about his own personal vision — a vision of spiritual values experienced by an aged Sioux medicine man during the Indian’s great time of travail and how he attempted to fulfill that vision and save his people. Black Elk had refused to relate this great vision to others, but accepted Neihardt immediately with the words: “He has been sent to learn what I know, and I will teach him.” First published in 1932 and heralded as “one of the greatest books about the life of the American Indian.” This publication is now in its tenth printing and has been translated into eight languages.

- Storm, Hyemeyohsts, Seven Arrows. Ballantine Books: New York, 1972. 374 pp. $7.95.

A full-blooded Cheyenne philosopher, H. Storm presents the parables passed down through countless generations of his people. Almost entirely allegorical in form, these stories are constructed in the same manner in which his Spiritual Fathers received them from their Fathers and on down to the Seven Great Grandfathers of the Universe.

“Come sit with me, and let us smoke the Pipe of Peace in Understanding. Let us Touch. Let us, each to the other, be a Gift as is the Buffalo. Sit here with me, each of you as you are in your own perceiving of yourself, as Mouse, Wolf, Coyote, Weasel, Fox, or Prairie Bird. Let me see through your eyes. Let us teach each other here in this Great Lodge of the People, this Sun Dance, of each of the Ways on this Great Medicine Wheel, our Earth.” [p. 1]

- Waters, Frank, Book of the Hopi. Ballantine Books: New York, 1963. 423 pp., $1.95.

The material for this book came from some thirty elders of the Hopi Indian Tribe in northern Arizona. As they reveal for the first time the essence of their creation, their emergences from previous worlds, their migration over this continent and their world-view of life, deeply religious in nature, they remind us that “we must attune ourselves to the need for inner change if we are to avert a cataclysmic rupture between our minds and hearts; the spiritual and material; the conscious and unconscious.” The word “Hopi” means peace. And as a People of Peace they speak not as a defeated, little minority in the richest and most powerful nation on earth, but as a Chosen People of the North American Spiritual Movement. And we are the richer for it, if we can but find the necessary degree of humility to listen.

NOTE: The above highly recommended books are excellent sources for continued study of this subject. However, they should not be ordered from HRA, since we do not stock copies for sale.

“If you have a sense of opposition — that is, if you feel contempt for others – you’re in a perfect position to receive their contempt. The idea is to not be a receiver… It’s a mistake to think of any group or person as an opponent, because when you do, that’s what the group or person will become. It’s more useful to think of every other person as another you – to think of every individual as a representative of the universe.” — from Rolling Thunder, p. 244.

“When an Indian prays he doesn’t read a lot of words out of a book. He just says a very short prayer. If you say a long one you won’t understand yourself what you are saying. And so the last thing I can teach you, if you want to be taught by an old man living in a dilapidated shack, a man who went to the third grade for eight years, is this prayer, which I use when I am crying for a vision: “Wakan Tanka, Tunkashila, onshimala… Grandfather Spirit, pity me, so that my people may live.” — from Lame Deer p. 255.

GETTING WHAT WE PRAY FOR

THE PAIUTE INDIAN VIEW

[Reprinted from Max Freedom Long’s HUNA VISTAS 42, p. 7; February, 1963.]

Mary Austin, in her autobiography, Earth Horizon, speaks of her great need to find a way to pray which would get definite answers. She studied the prayer methods of the Paiute Indian medicine men and learned from them the ritual way to pray to the “Wakonda” or “Friend-of-the-soul-of-man.”

We, too, as HRAs are looking for a lead that might take us to the knowledge of how best to play our parts, as middle and low selves, in the work to be performed by the team of three selves as a whole. The kahunas believed in NORMAL LIVING in all respects, so we may rule out at once the methods of the hermits in which sex and food were looked upon as wicked things which God had made by mistake or which had been engineered by the Devil, and which kept the man from his proper contact with his God. The records tell us that the hermits in their caves, fasting and torturing their bodies, got nothing better than strange hallucinationary (sic) dreams or visions which were of little value. Some became obsessed. Like the Yogi following a similar method, not one “set the world afire” with discoveries. In the field of mental action, reason precludes the mystical unless we accept the Huna idea of the prayer-action method and use it. As to the High Self Mother-Father, we have the hint that they are activated by love, and from this we may draw the conclusion that if we, as the lower pair of selves, can generate love appropriate to our lower levels of life , we might better fall into step with the High Self Parental Pair to aid creative action in which more good is accomplished.

Let us go back to Mary Austin’s book (p. 276) and see what she wrote of the methods used by the Paiute Indian medicine man who introduced her to High Self as the Wakonda, and which she had known in childhood as her own “I Mary” who was wiser and stronger and who would come to her aid when called in times of trouble. She reports questioning the medicine man: “Do you truly get what you pray for?” ‘Surely, if you pray right.’ But the answer to what was ‘right’ in the Paiute practice involved an immense amount of explanation. Prayer, to the Medicine Man, had nothing to do with emotion; it was an act, an outgoing act of the inner self toward something, not a god, toward a responsive activity in the world about you, designated as ‘The-Friend-of-the-Soul-of-Man;’ Wakonda, to use a term adopted by ethnologists — the effective principle of the created universe. This inner act was to be outwardly expressed in bodily acts, in words, in music, rhythm, color, whatever medium served the immediate purpose, or all of them. Prayer, so understood and instigated, acted with the sureness of a chemical combination. It was the nature of the Wakonda so worked upon not to be able to do otherwise than to act reciprocally.” Here we have the complete faith of the Indian, and it was well that this faith was enduring, for the prayers for rain in the arid reservation lands have been danced, chanted and illustrated in sand paintings and costumes for centuries, with the prayers so seldom answered, and always with the excuse which left faith unbroken, “The prayer was not made right.”